I myself have an unbearably vulgar name, am well aware of the fact, and have no plans to change it. But I remain extremely interested in people’s names.

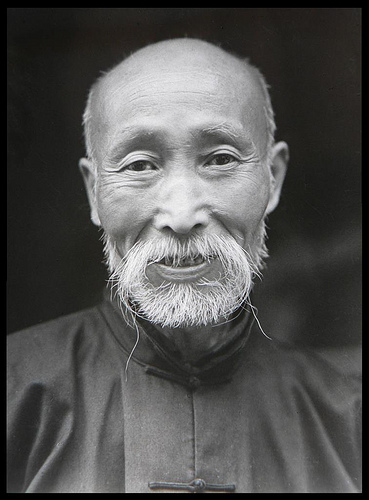

To give someone a name is a simple and small-scale act of creation. When the patriarch of days gone by would sit in winter with his feet propped up on a foot-warming brazier, smoking a water-pipe, and pick out a name for a newly arrived grandson, his word was all. If the boy was called Guang-mei (Brighten the Threshold), he would end up doing his best to redound honor on the gates of the family house. If he was called Zhuyin (Ancestral Privilege) or Chengzu (Indebted to the Ancestor), he would be compelled always to remember his forebears. If he was called Hesheng (Lotus Born), his life would take on something of the coloring of a pond in June. Characters in novels aside, there aren’t many people whose names adequately describe what they are like in reality (and often the opposite is the case and the name represents something they need or lack– nine of ten poor people have names like Jingui [Gold Precious], Ah Fu [Richie], Dayou [Have a Lot]). But no matter how or in what manner, names inevitably become entangled with appearance and character in the process of creating a complete impression of a person. And this is why naming is a kind of creation.

I would like to give someone a name, even though I’ve yet to have the opportunity to do so….

—Chinese novelist Eileen Chang (1920-1995) in her essay “What is essential is that names be right” from Written on Water (2005), translated from her book Liuyan (1968) by Andrew F. Jones. The essays were written in wartime Shanghai. The title refers to a famous quotation of Confucius.

Thank you to Nick who found the Chinese (below).

我自己有一个恶俗不堪的名字,明知其俗而不打算换一个,可是我对于人名实在是非常感到兴趣的。

为人取名字是一种轻便的,小规模的创造。旧时代的祖父,冬天两脚搁在脚炉上,吸着水烟,为新添的孙儿取名字,叫他什么他就是什么。叫他光楣,他就是努力光大门楣;叫他祖荫,叫他承祖,他就得常常记起祖父;叫他荷生,他的命里就多了一点六月的池塘的颜色。除了小说里的人,很少有人是名副其实的,(往往适得其反,名字代表一种需要,一种缺乏。穷人十有九个叫金贵,阿富,大有。)但是无论如何,名字是与一个人的外貌品性打成一片,造成整个的印象的。因此取名是一种创造。

我喜欢替人取名字,虽然我还没有机会实行过。。。